|

There

was once a regular student, who lived in a garret, and had no

possessions. And there was also a regular huckster, to whom the

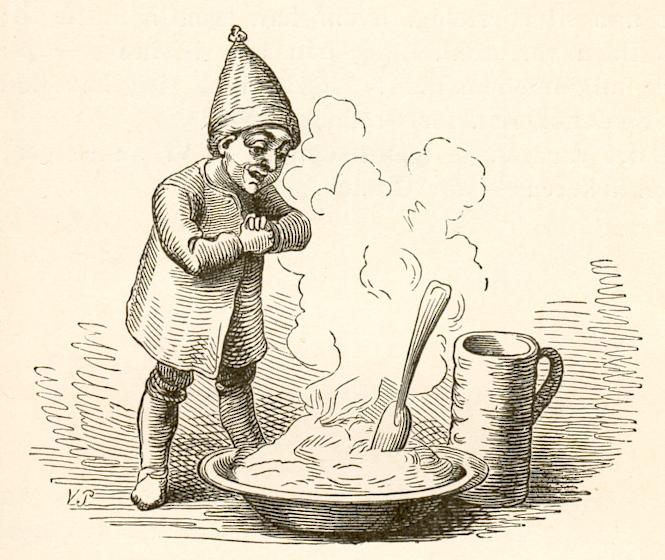

house belonged, and who occupied the ground floor. A goblin lived

with the huckster, because at Christmas he always had a large dish

full of jam, with a great piece of butter in the middle. The

huckster could afford this; and therefore the goblin remained with

the huckster, which was very cunning of him.

One evening the student came into the shop through the back door to

buy candles and cheese for himself, he had no one to send, and

therefore he came himself; he obtained what he wished, and then the

huckster and his wife nodded good evening to him, and she was a

woman who could do more than merely nod, for she had usually plenty

to say for herself. The student nodded in return as he turned to

leave, then suddenly stopped, and began reading the piece of paper

in which the cheese was wrapped. It was a leaf torn out of an old

book, a book that ought not to have been torn up, for it was full of

poetry.

“Yonder lies some more of the same sort,” said the huckster: “I gave

an old woman a few coffee berries for it; you shall have the rest

for sixpence, if you will.”

“Indeed I will,” said the student; “give me the book instead of the

cheese; I can eat my bread and butter without cheese. It would be a

sin to tear up a book like this. You are a clever man; and a

practical man; but you understand no more about poetry than that

cask yonder.”

This was a very rude speech, especially against the cask; but the

huckster and the student both laughed, for it was only said in fun.

But the goblin felt very angry that any man should venture to say

such things to a huckster who was a householder and sold the best

butter. As soon as it was night, and the shop closed, and every one

in bed except the student, the goblin stepped softly into the

bedroom where the huckster's wife slept, and took away her tongue,

which of course, she did not then want. Whatever object in the room

he placed his tongue upon immediately received voice and speech, and

was able to express its thoughts and feelings as readily as the lady

herself could do. It could only be used by one object at a time,

which was a good thing, as a number speaking at once would have

caused great confusion. The goblin laid the tongue upon the cask, in

which lay a quantity of old newspapers.

“Is it really true,” he asked, “that you do not know what poetry

is?”

“Of course I know,” replied the cask: “poetry is something that

always stand in the corner of a newspaper, and is sometimes cut out;

and I may venture to affirm that I have more of it in me than the

student has, and I am only a poor tub of the huckster's.”

Then the goblin placed the tongue on the coffee mill; and how it did

go to be sure! Then he put it on the butter tub and the cash box,

and they all expressed the same opinion as the waste-paper tub; and

a majority must always be respected.

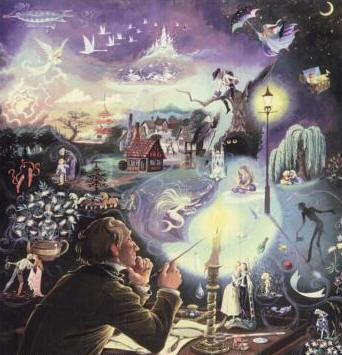

“Now I shall go and tell the student,” said the goblin; and with

these words he went quietly up the back stairs to the garret where

the student lived. He had a candle burning still, and the goblin

peeped through the keyhole and saw that he was reading in the torn

book, which he had brought out of the shop. But how light the room

was! From the book shot forth a ray of light which grew broad and

full, like the stem of a tree, from which bright rays spread upward

and over the student's head. Each leaf was fresh, and each flower

was like a beautiful female head; some with dark and sparkling eyes,

and others with eyes that were wonderfully blue and clear. The fruit

gleamed like stars, and the room was filled with sounds of beautiful

music. The little goblin had never imagined, much less seen or heard

of, any sight so glorious as this. He stood still on tiptoe, peeping

in, till the light went out in the garret. The student no doubt had

blown out his candle and gone to bed; but the little goblin remained

standing there nevertheless, and listening to the music which still

sounded on, soft and beautiful, a sweet cradle-song for the student,

who had lain down to rest.

“This is a wonderful place,” said the goblin; “I never expected such

a thing. I should like to stay here with the student;” and the

little man thought it over, for he was a sensible little spirit. At

last he sighed, “but the student has no jam!” So he went down stairs

again into the huckster's shop, and it was a good thing he got back

when he did, for the cask had almost worn out the lady's tongue; he

had given a description of all that he contained on one side, and

was just about to turn himself over to the other side to describe

what was there, when the goblin entered and restored the tongue to

the lady. But from that time forward, the whole shop, from the cash

box down to the pinewood logs, formed their opinions from that of

the cask; and they all had such confidence in him, and treated him

with so much respect, that when the huckster read the criticisms on

theatricals and art of an evening, they fancied it must all come

from the cask.

But after what he had seen, the goblin could no longer sit and

listen quietly to the wisdom and understanding down stairs; so, as

soon as the evening light glimmered in the garret, he took courage,

for it seemed to him as if the rays of light were strong cables,

drawing him up, and obliging him to go and peep through the keyhole;

and, while there, a feeling of vastness came over him such as we

experience by the ever-moving sea, when the storm breaks forth; and

it brought tears into his eyes. He did not himself know why he wept,

yet a kind of pleasant feeling mingled with his tears. “How

wonderfully glorious it would be to sit with the student under such

a tree;” but that was out of the question, he must be content to

look through the keyhole, and be thankful for even that.

There he stood on the old landing, with the autumn wind blowing down

upon him through the trap-door. It was very cold; but the little

creature did not really feel it, till the light in the garret went

out, and the tones of music died away. Then how he shivered, and

crept down stairs again to his warm corner, where it felt home-like

and comfortable. And when Christmas came again, and brought the dish

of jam and the great lump of butter, he liked the huckster best of

all.

Soon after, in the middle of the night, the goblin was awoke by a

terrible noise and knocking against the window shutters and the

house doors, and by the sound of the watchman's horn; for a great

fire had broken out, and the whole street appeared full of flames.

Was it in their house, or a neighbor's? No one could tell, for

terror had seized upon all. The huckster's wife was so bewildered

that she took her gold ear-rings out of her ears and put them in her

pocket, that she might save something at least. The huckster ran to

get his business papers, and the servant resolved to save her blue

silk mantle, which she had managed to buy. Each wished to keep the

best things they had. The goblin had the same wish; for, with one

spring, he was up stairs and in the student's room, whom he found

standing by the open window, and looking quite calmly at the fire,

which was raging at the house of a neighbor opposite. The goblin

caught up the wonderful book which lay on the table, and popped it

into his red cap, which he held tightly with both hands. The

greatest treasure in the house was saved; and he ran away with it to

the roof, and seated himself on the chimney. The flames of the

burning house opposite illuminated him as he sat, both hands pressed

tightly over his cap, in which the treasure lay; and then he found

out what feelings really reigned in his heart, and knew exactly

which way they tended. And yet, when the fire was extinguished, and

the goblin again began to reflect, he hesitated, and said at last,

“I must divide myself between the two; I cannot quite give up the

huckster, because of the jam.”

And this is a representation of human nature. We are like the

goblin; we all go to visit the huckster “because of the jam.”

END |

![]()

![]() BACK

TO CHRISTMAS FAIRY TALES - INDEX

BACK

TO CHRISTMAS FAIRY TALES - INDEX