|

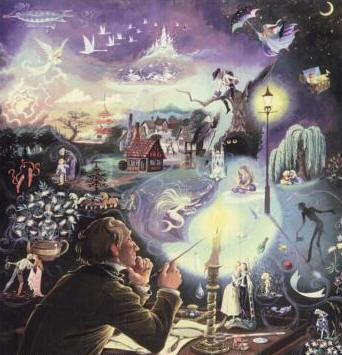

You know the Goblin, but do you know the Woman-the Gardener's wife?

She was very well read and knew poems by heart; yes, and she could

write them, too, easily, except that the rhymes-"clinchings," as she

called them-gave her a little trouble. She had the gift of writing

and the gift of speech; she could very well have been a parson or at

least a parson's wife.

"The earth is beautiful in her Sunday gown," she said, and this

thought she had expanded and set down in poetic form, with "clinchings,"

making a poem that was so long and lovely.

The Assistant Schoolmaster, Mr. Kisserup (not that his name matters

at all), was her nephew, and on a visit to the Gardener's he heard

the poem. It did him good, he said, a lot of good. "You have soul,

Madam," he said.

"Stuff and nonsense!" said the Gardener. "Don't be putting such

ideas in her head! Soul! A wife should be a body, a good, plain,

decent body, and watch the pot, to keep the porridge from burning."

"I can take the burnt taste out of the porridge with a bit of

charcoal," said the Woman. "And I can take the burnt taste out of

you with a little kiss. You pretend you don't think of anything but

cabbage and potatoes, but you love the flowers, too." Then she

kissed him. "Flowers are the soul!"

"Mind your pot!" he said, as he went off to the garden. That was his

pot, and he minded it.

But the Assistant Schoolmaster stayed on, talking to the woman. Her

lovely words, "Earth is beautiful," he made a whole sermon of, which

was his habit.

"Earth is beautiful, and it shall be subject unto you! was said, and

we became lords of the earth. One person rules with the mind, one

with the body; one comes into the world like an exclamation mark of

astonishment, another like a dash that denotes faltering thought, so

that we pause and ask, why is he here? One man becomes a bishop,

another just a poor assistant schoolmaster, but everything is for

the best. Earth is beautiful and always in her Sunday gown. That was

a thought-provoking poem, Madam, full of feeling and geography!"

"You have soul, Mr. Kisserup," said the Woman, "a great deal of

soul, I assure you. After talking with you, one clearly understands

oneself."

And so they talked on, equally well and beautifully. But out in the

kitchen somebody else was talking, and that was the Goblin, the

little gray-dressed Goblin with the red cap-you know the fellow. The

Goblin was sitting in the kitchen, acting as pot watcher. He was

talking, but nobody heard him except the big black Pussycat-"Cream

Thief," the Woman called him.

The Goblin was mad at her because he had learned she didn't believe

in his existence. Of course, she had never seen him, but with all

her reading she ought to have realized he did exist and have paid

him a little attention. On Christmas Eve she never thought of

setting out so much as a spoonful of porridge for him, though all

his ancestors had received that, and even from women who had no

learning at all. Their porridge used to be so swimming with cream

and butter that it made the Cat's mouth water to hear about it.

"She calls me just a notion!" said the Goblin. "And that's more than

I can understand. In fact, she simply denies me! I've listened to

her saying so before, and again just now in there, where she's

driveling to that boy whipper, that Assistant Schoolmaster. I say

with Pop, 'Mind the pot!' That she doesn't do, so now I am going to

make it boil over!"

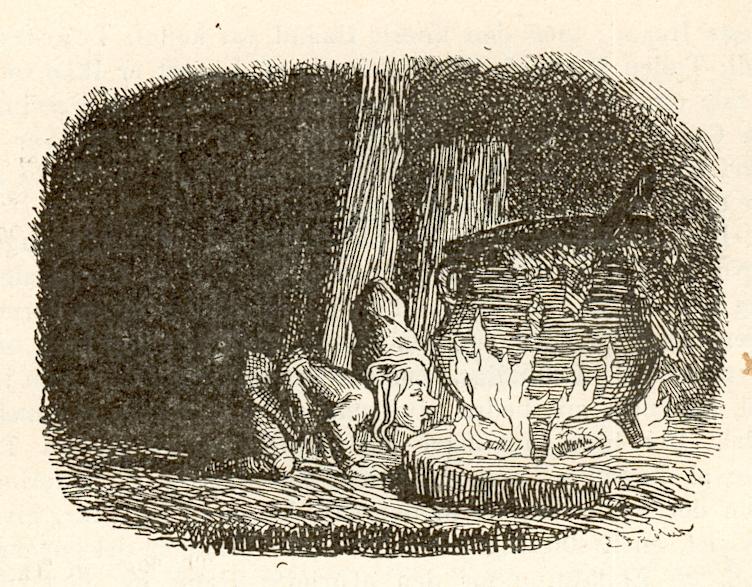

And the Goblin blew on the fire till it burned and blazed up. "Surre-rurre-rup!"

And the pot boiled over.

"And now I'm going to pick holes in Pop's socks," said the Goblin.

"I'll unravel a large piece, both in toe and heel, so she'll have

something to darn; that is, if she is not too busy writing poetry.

Madam Poetess, please darn Pop's stocking!"

The Cat sneezed; he had caught a cold, though he always wore a fur

coat.

"I've opened the door to the larder," said the Goblin. "There's

boiled cream in there as thick as paste. If you won't have a lick I

will."

"If I am going to get all the blame and the whipping for it,

anyway," said the Cat, "I'll lick my share of the cream."

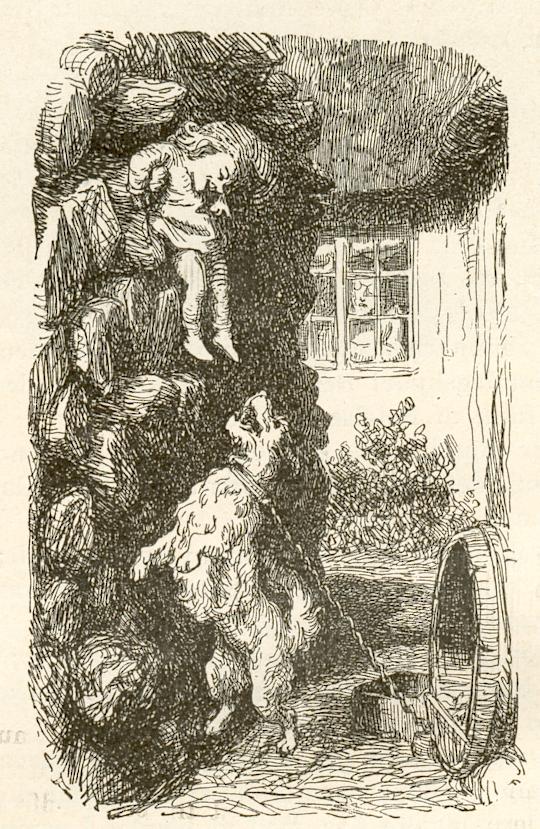

"First a lick, then a kick!" said the Goblin. "But now I'm off to

the Assistant Schoolmaster's room, where I'll hang his suspenders on

the mirror, put his socks into the water pitcher, and make him think

the punch was too strong and has his brain in a whirl. Last night I

sat on the woodpile by the kennel. I have a lot of fun teasing the

watchdog; I let my legs dangle in front of him. The dog couldn't

reach them, no matter how hard he jumped; that made him mad, he

barked and barked, and I dingled and dangled; we made a lot of

noise! The Assistant Schoolmaster woke up and jumped out of bed

three times, but he couldn't see me, though he was wearing his

spectacles. He always sleeps with his spectacles on."

"Say mew when you hear the Woman coming," said the Cat. "I'm a

little deaf. I don't feel well today."

"You have the licking sickness," said the Goblin. "Lick away; lick

your sickness away. But be sure to wipe your whiskers, so the cream

won't show on it. I'm off to do a little eavesdropping."

So the Goblin stood behind the door, and the door stood ajar. There

was nobody in the parlor except the Woman and the Assistant

Schoolmaster. They were discussing things which, as the Assistant

Schoolmaster so nobly observed, ought to rank in every household

above pots and pans-the Gifts of the Soul.

"Mr. Kisserup," said the Woman, "since we are discussing this

subject, I'll show you something along that line which I've never

yet shown to a living soul-least of all a man. They're my smaller

poems; however, some of them are rather long. I have called them 'Clinchings

by a Danneqvinde.' You see, I am very fond of old Danish words!"

"Yes, we should hold onto them," said the Assistant Schoolmaster.

"We should root the German out of our language."

"That I am doing, too!" said the Woman. "You'll never hear me speak

of Kleiner or Butterteig;no, I call them fatty cakes and paste

leaves."

Then she took a writing book, in a light green cover, with two

blotches of ink on it, from her drawer.

"There is much in this book that is serious," she said. "My mind

tends toward the melancholy. Here is my 'The Sign in the Night,' 'My

Evening Red,' and 'When I Got Klemmensen'-my husband; that one you

may skip over, though it has thought and feeling. 'The Housewife's

Duties' is the best one-sorrowful, like all the rest; that's my best

style. Only one piece is comical; it contains some lively

thoughts-one must indulge in them occasionally-thoughts about-now,

you mustn't laugh at me-thoughts about being a poetess! Up to now it

has been a secret between me and my drawer; now you know it, too,

Mr. Kisserup. I love poetry; it haunts me; it jeers, advises, and

commands. That's what I mean by my title, 'The Little Goblin.' You

know the old peasants' superstitions about the Goblin who is always

playing tricks in the house. I myself am the house, and my poetical

feelings are the Goblin, the spirit that possesses me. I have

written about his power and strength in 'The Little Goblin'; but you

must promise with your hands and lips never to give away my secret,

either to my husband or to anyone else. Read it loud, so that I can

tell if you understand the meaning."

And the Assistant Schoolmaster read, and the Woman listened, and so

did the little Goblin. He was eavesdropping, you'll remember, and he

came just in time to hear the title 'The Little Goblin.'

"That's about me!" he said. "What could she have been written about

me? Oh, I'll pinch her! I'll chip her eggs, and pinch her chickens,

and chase the fat off her fatted calf! Just watch me do it!"

And then he listened with pursed lips and long ears; but when he

heard of the Goblin's power and glory, and his rule over the woman

(she meant poetry, you know, but the Goblin took the name

literally), the little fellow began grinnning more and more. His

eyes brightened with delight; then the corners of his mouth set

sternly in lines of dignity; he drew himself up on his toes a whole

inch higher than usual; he was greatly pleased with what was written

about the Little Goblin.

"I've done her wrong! The Woman has soul and fine breeding! How, I

have done her wrong! She has put me into her 'Clinchings,' and

they'll be printed and read. Now I won't allow the Cat to drink her

cream; I'll do that myself! One drinks less than two, so that'll be

a saving; and that I shall do, and pay honor and respect to the

Woman!"

"He's a man all right, that Goblin," said the old Cat. "Just one

sweet mew from the Woman, a mew about himself, and he immediately

changes his mind! She is a sly one, the Woman!"

But the Woman wasn't sly; it was just that the Goblin was a man.

If you can't understand this story, ask somebody to explain it to

you; but don't ask the Goblin or the Woman, either.

END |

![]()

![]() BACK

TO CHRISTMAS FAIRY TALES - INDEX

BACK

TO CHRISTMAS FAIRY TALES - INDEX